Population Growth Plummets - Wednesday Wrapup Dec. 30, 2020

US population grows at slowest rate since WWII; an idea for reviving trust and the arts and culture sector; and the persistence of the immigration and wage debate.

1. Slow Growth Ahead

Population growth has all but ground to a halt, according to new data from the US Census Bureau. The United States added only 1.1 million people between July 2019 and July 2020, compared to 1.5 million during the same period the year before and an average of well over 2 million earlier in the decade.

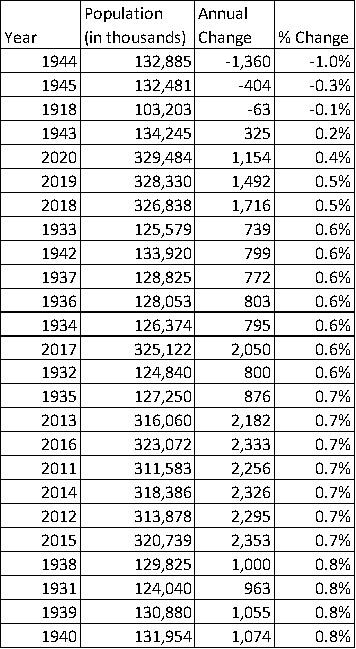

While most headlines have covered internal state-to-state moves, the slowdown in overall growth will have larger ripple effects. Since 1900, there have been only four years with slower population growth than 2020 - three of them were during World War II and one of them, 1918, during World War I and an Influenza pandemic. (I couldn’t easily find pre-1900 annual estimates)

It would be easy to shrug this off as a temporary, pandemic-driven blip, but the pandemic only affected 4 of the 12 months measured here, and 2018 and 2019 showed nearly as slow growth. In fact, of the 25 years with the slowest population growth, all came either during World Wars, the Great Depression years of the 1930s, or the 2010s.

25 Slowest Years for US Population Growth since 1900

Record low birth rates and increasing immigration restrictions have combined to slow growth. And while rapid population growth comes with its own obvious problems, slow population growth may be more economically damaging in the long run. A look at Japan’s aging population and negative growth rates and that country’s economic stagnation since about 1990 give us a glimpse into the long-term consequences. Ultimately, lower population growth will lead to less long-term investment as businesses project fewer future customers and less innovation as fewer people means less research and development. While a post-WWII-scale baby boom seems unlikely in the modern era, the combination of skilled immigration promotion and child-care assistance for young families is gaining support (in general terms) in policy circles. Matthew Yglesias’ One Billion Americans is one example (I reviewed Yglesias’ book for another publication, which should be out soon)

Three states - Texas, Florida and California - accounted for 45% of population growth over the decade. While Texas’ and Florida’s growth was steady throughout the decade, California’s growth began a sharp reversal starting around 2015, and came to a stop in 2019. While the Golden State had been adding more than 300,000 people every year between 2008 and 2015, by 2019 only 147 net newcomers arrived in California and in 2020, the state lost nearly 70,000 people.

Connecticut, Illinois, Mississippi, New York, Vermont and West Virginia were the only six states to lose population over the decade. New York’s net growth peaked in 2011 at about 100,000 before declining each year and turning into negative growth after 2015. Neighboring Connecticut’s population also began to drop in 2014. Illinois followed a similar pattern, with growth peaking in 2007, declining, then turning negative as of 2014. Mississippi’s growth fluctuated before turning sharply negative in 2018, similar to Vermont, though Vermont’s recent losses are not as extreme. West Virginia lost each year since 2011.

Growth rates slowed down across the board in 2020 with many states in the Northeast and Midwest (as well as California, Louisiana, and Mississippi) slipping into negative growth. (One interesting sidenote here is Michigan. While Michigan lost population in 2020, it had reversed a longer-term decline. After losing about 75,000 in the 2000s, Michigan added back more than 88,000 in the 2010s.)

The rate of growth in some Sunbelt states like the Carolinas, Colorado, Georgia, and Virginia, while still adding significant numbers, also began to slow.

Thirteen states saw their growth rates speed up in 2020, most notably Texas, Tennessee, Florida, and Arizona. Smaller states with significant increases in growth rates included Montana, Oklahoma and Kansas.

Overall, the South continues to be the nation’s fastest-growing region, driven primarily by Texas and Florida, which are sponges for migrants from other states as well as immigrants. While the South accounted for about 59% of the nation’s growth over the 2010s, it accounted for more than 80% in 2019-2020.

Larger international gateway states like New York and California, which have been reliant on international immigration to grow, have seen negative growth particularly after about 2017.

There’s a lot to unpack here about immigration restrictions, lower birth rates, and corporate site location decisions. (of note: Florida and Texas both have no state income tax) We’re likely to see at least one more year of even slower growth as the 2021 numbers will reflect July 2020-June 2021, a time period likely to be mostly affected by the pandemic. We also will have to wait a while to see the breakdown of growth by births, immigration and migration at the state level.

But we can say a few things for certain:

The “California exodus” is real and, with lower immigration and internal migration, newcomers are not backfilling.

Rural depopulation is showing up at a large scale in Mississippi, West Virginia and to a lesser extent Vermont.

Southern cities in Texas and Florida will begin to see pressures on the housing market and infrastructure to keep pace with the growth.

Hopefully, they will respond by investing in infrastructure and streamlining building processes to avoid the type of price spikes we saw in the places these newcomers might be leaving.

2. Challenges in the Arts and Culture Sector

Cleaning up the home office this week, I came across the playbill for the only Broadway show I’ve ever attended. We started to throw it out, but looking at the date - March 3, 2020 - we thought it was worth hanging onto. That was the same day health officials announced the first coronavirus case in Manhattan. Nine days later, the theaters shut down and haven’t opened since.

The country has shed more than 587,000 arts, entertainment, and recreation jobs since March - a 26% decline according to the Current Employment Survey. While larger total numbers of food service jobs have disappeared (about 1.4 million), that accounts for about 12% of employment in the food service industry. The coronavirus has been devastating for all in-person services. Even as restaurants have returned to limited capacity, some performance arts still remain completely closed and are likely to be the last sector to open when the pandemic subsides.

It’s never been easy to make a living as an artist. Actors, musicians, and freelance writers were stringing gigs together before the “gig economy” was a term. While platforms for individual creators like Patreon have provided a lifeline to some homebound musicians or artists, the nature of these platforms tends to favor artists with already large followings and doesn’t always translate to money.

The most recent COVID relief package includes $15 billion for struggling arts and music venues, particularly ones most reliant on ticket sales, sales which have been nonexistent since that week in early March. That’s welcome news for the struggling industry, but won’t fill the full gap. A Brookings study of “creative industries” estimated total losses of more than $150 billion in sales.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, when the publishing industry faced 25% unemployment, the Federal Writers Program employed about 7,000 laid off writers and newspaper reporters and the Federal Theater Project produced about 800 plays and captured the voices of the last living generation of enslaved people before being shuttered in the runup to WWII. A similar Federal Art Project commissioned murals in public buildings throughout the country.

In arguing for a revamped FWP, David Kipen notes that the program’s state and city guidebooks highlighted the voices of ordinary Americans, benefitting not only the writers and artists who made a living from it but to all Americans by introducing them to their “multifarious, astonishing, broken country.”

It’s hard to see today’s federal government establishing a similar program. First, coronavirus restrictions limit large-scale in-person interviewing and art creation (Digital storytelling presents opportunities here). More than that, though, political consensus in Washington would be a hurdle. (The original FWP faced political challenges as well. The House Un-American Activities Committee was a thorn in the program’s side.) But it’s worth thinking about what a modern federal arts program might achieve.

Societal trust, though still higher in the US than in some developed countries, is declining. At the same time, arts education opportunities in schools have by some reports been phased out under budget cuts. Rural communities in particular express a strong sense of alienation from “media.” Directing some arts and humanities funding to help these communities tell their own “stories” through school programs, could be a way to begin to restore some of that trust.

EXTRAS. A Followup on Local Government Employment, An Immigration Debate

Last week, I wrote about declines in state and local budgets and the lack of general aid in the new COVID package. (Link here, second item) A new report from Brookings, released late last week, noted that earlier projections of state and local tax losses might have been too pessimistic, particularly in states which rely on tax codes with increasing rates for higher-income earners. Still, employment declines have been greater than during the great recession, particularly in the education sector. While much of the employment loss is due to schools being shut down, losses in the higher education sector, particularly in light of lower enrollments, will be an telling trend to track.

The lower population growth I mentioned in the first item of this newsletter, combined with the upcoming change in presidential administration, has revived a perennial debate in American policy circles - Does immigration increase or lower wages for native-born workers? Oren Cass’ center-right American Compass think tank, which has bucked the GOP orthodoxy with its thoughts on worker power and industrial policy, argues that looser borders will ultimately drive down wages for the lowest-skilled Americans, running counter to Matthew Yglesias’ argument in One Billion Americans. Bloomberg economist Noah Smith counters that by boosting overall labor demand, even the lowest skilled immigration has little effect on native-born wages. His summary of a dozen papers from multiple countries is linked here. As Smith points out, economics papers are not likely to change anyone’s mind on such a heated topic, but expect to hear more about immigration policy in the coming years.