Wednesday wrapup - Dec. 23, 2020

The stimulus is more than your check, state and local governments are in crisis, and community college enrollment drops stunt economic mobility. Also - new writing, analysis, and a podcast.

1. No, it’s not “just $600”

A second round of COVID relief finally made it through Congress this week. The $900 billion package weighed in at a hefty 5,000+ pages. There’s a lot in there, from broadband funding to airline payroll support. Politico provides the bullet points here.

The bulk of the bill, about $611 billion, contains three big programs - additional Payroll Protection Program funds for small businesses, a $300/week federal supplement for unemployment insurance, and a second round of stimulus checks, this time for $600.

You probably heard about the $600. If you spend any time on social media, you probably came across some tweets like the one below. It’s from former Clinton Administration Secretary of Labor Robert Reich lamenting the supposedly feeble response to coronavirus relief in comparison to other countries.

The problem - he’s just wrong. The more than $3 trillion spent on COVID relief so far accounts for about 18% of GDP, higher than France’s 16% and double UK’s 9%, according to an analysis by Turkish economist Ceyhun Elgin. While it’s true that European countries have generally higher levels of existing social supports, the level of unemployment support and federal spending is unmatched since World War II.

More directly to Reich’s tweet, unemployment supplements of $600 per week from March through July came on top of existing state programs. The combination of these two programs provided about 110% replacement of average income for unemployed workers in most states (up to 130% in some). This helped bolster consumer spending among lower-income households. That boost in spending has since waned as coronavirus cases rose this fall. Economist Ernie Tedeschi estimates the new $300/week supplement will replace, on average, around 85% of unemployed workers’ pay. Tedeschi’s entire thread is worth reading.

Why did the “just $600” travel so well on Twitter? A few weeks ago, I reviewed Robert Shiller’s new book Narrative Economics. The gist of the book is that economists should pay more attention to stories, because they drive more economic decision-making than the math-minded think. Narratives don’t exist in isolation. People interpret new information through existing stories. In this case, the narrative of the stingy American safety net in comparison to more generous EU nations has become common, especially in left-leaning circles. The universal nature of the $600 direct payments - even people who kept their jobs will get them - makes it easy to ignore the rest of the policy.

Beyond being simply misleading, the “just $600” narrative is counterproductive for the policymakers and organizations who would like to expand the social safety net more permanently. An honest analysis of unemployment supplements and their role in preventing a deep recessionary spiral could open more productive conversations on how states or the federal government might balance extended unemployment or even some form of universal payments with the needs of employers in a more fully functioning, post-pandemic economy.

So far, judging from Twitter engagement numbers, the posters looking to get their more nuanced takes out there are swimming upstream.

2. MIA: State and Local Aid

One key provision missing from the second COVID-19 relief package is aid to state and local governments. After some Republicans campaigned against what they called “blue-state bailouts,” Democrats dropped the aid request in the final compromise in exchange for Republicans leaving out liability shield legislation for businesses open during the pandemic.

States are projecting major budget deficits in the coming fiscal year after declines in consumer spending on services, combined with layoffs and wage cuts, are likely to cut into two of their major funding sources - sales and income taxes. While property tax collections account for more direct revenue in cities and towns, the hit to local hotel and visitor taxes, not to mention cuts to local services, will also constrain municipal budgets.

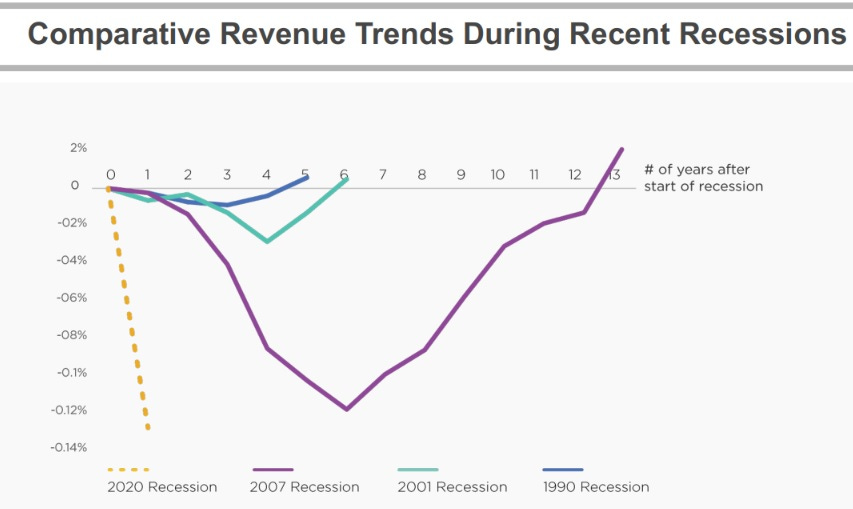

The true impact of state and local budget crunches will start later and lag longer than the private-sector recession. With most cities and many states working on July-June fiscal calendars, virus impacts affected a little more than a quarter of the previous fiscal year. The average city government expects a 13% decline in general fund revenue this fiscal year (FY21) compared to last, according to the National League of Cities. This is likely to compound in fiscal year 2022, leading to continued budget cuts, even after a private sector rebound starts. Local government revenues have taken an increasingly long time to rebound from recessions. According to the NLC chart below, overall city government revenues had only fully rebounded from the 2007-09 recession last year.

State and local governments employ 13% of the national workforce. The sector has shed more than 1.2 million jobs since March. In some rural or distressed counties without strong private-sector industrial bases, college towns, and state capitals, the impacts and spillover effects of local and state government employment are key economic drivers.

There are legitimate arguments to be made about pension reform and consolidation of some local government functions in legacy cities, but the fact is local governments have already found a lot of efficiencies and cut back on services. State and local government employment has remained relatively flat since before the 2007-09 recession.

Unlike the federal government, most states and municipalities are bound to balance their budgets. Borrowing to fill budget gaps is off the table, meaning they will have to either raise tax rates or cut services. With employment still down and virus concerns keeping people at home, higher taxes seem unlikely to help. Without future aid, services and employment could drag through 2023.

3. Community College Enrollment Plummets

Once or twice a year, I teach a Recent American History class at a local community college. Classes consist of a varied group. There are high school students earning early college credits, recent grads juggling jobs and family responsibilities, and empty nesters looking to finish what they started decades before. The conversations are always engaging.

Community college enrollment usually runs counter to broader economic conditions. Laid off workers return to community college to upgrade their skills and high school students who might have gone right to work in a better economy wait out the recession in the classroom. The opposite has happened this time around. New data from the National Student Clearinghouse show 544,000 fewer students enrolled in community college in Fall 2020, a 10% drop from the fall before. New student enrollment declined 21%. Overall college enrollment was down just over 2% with freshman enrollment declining 13%.

About 40% of high school graduates who seek additional education start at a public two-year school. That percentage is higher among first-generation students and students from low-income backgrounds. And while, according to Opportunity Insights research, public four-year colleges tend to propel a higher proportion of lower-income students into the middle class than community colleges, two-year institutions’ open enrollment policies provide an important public good for the widest variety of students (You can explore specific college mobility metrics here). In addition, measurement issues can misrepresent community college success metrics, particularly for vocational-oriented programs, as Laura Ullrich, regional economist from the Charlotte Branch of the Richmond Federal Reserve details here. “Graduation” rates don’t always capture the value of students who take one or two skills-based classes to get a raise, for example, or who transfer to four-year schools before completing the two-year degree.

State support for higher education has already been a casualty of previous recessions, declining by more than $6.6 billion overall since 2008. The state budget crunches mentioned in the previous item could accelerate this trend. This decline has shifted more costs to students, though community colleges remain the most affordable higher education option. The COVID relief bill provides expanded access to Pell Grants to students from families making less than $60,000 annually, which should help extend access to more students. Broadband provisions could also help with rural students and other distance learners. But broader outreach to lower-income students from the high school class of 2020 will be needed, community college leaders say, to prevent a “lost generation” of community college students.

EXTRAS. New Writing, Analysis, and a Podcast Episode

In the December 2020 issue of Charlotte Magazine - I added a 13th chapter to my 12-part series on Charlotte history, “The Story of Charlotte.” This chapter was probably the most challenging as it advanced the city and region’s history from 2008 to 2016. Writing the history of a time and place you personally experienced as a more or less politically engaged adult was a new experience. When you write about the history of distant time periods, you get the benefit of others’ outlines of the events that were important and what seemed current at the time but wound up less enduring. I look forward to looking back on this piece in a few years to see how my interpretation might change. You can read the full series here. Illustrations from Kim Rosen really pulled the whole series together.

My team at the Charlotte Regional Business Alliance produced a detailed analysis of the Charlotte Region’s competitive advantages in manufacturing. While Charlotte is known as a banking town, the manufacturing industry contributes nearly as much - $26 billion - to the region’s economy as finance - $28 billion. I spoke with our lead researcher on the project, VP Antony Burton, about the report and the manufacturing sector more broadly in this CLT Alliance Talks podcast.