Are We "Stuck" or "Rooted?" - Wednesday Wrapup, Jan. 27, 2021

Why Americans are moving less than ever; California city takes big step to improve housing choice; newly recharged optimism for electrical vehicles; and a podcast with EV-maker Arrival.

1. Stuck, or Rooted, in Place?

Packing up and moving is an American pastime. From immigrant roots to Western expansion to the Great Migration of the early 20th century, the “big move” is a big part of middle-class family folklore and celebrity success stories.

One example this week came from the obituary of Larry King, who died at 87, and how he got his break in the radio industry in the 1950s.

Stories like this are becoming rare. As the tweeter makes clear, it seems implausible today, especially in the media industry. There are a lot of reasons for that - consolidation of media in major markets and decline of local media outlets, contracting out tasks like janitorial work (today the janitor would likely work for an outside company with little chance of informal interaction with decision-makers), and generally slower economic growth in the 2020s compared to the 1950s.

The main point here is that it all started with King’s willingness and ability to move the 1,200 miles from Brooklyn to Miami to start a low-wage job at a smaller outlet.

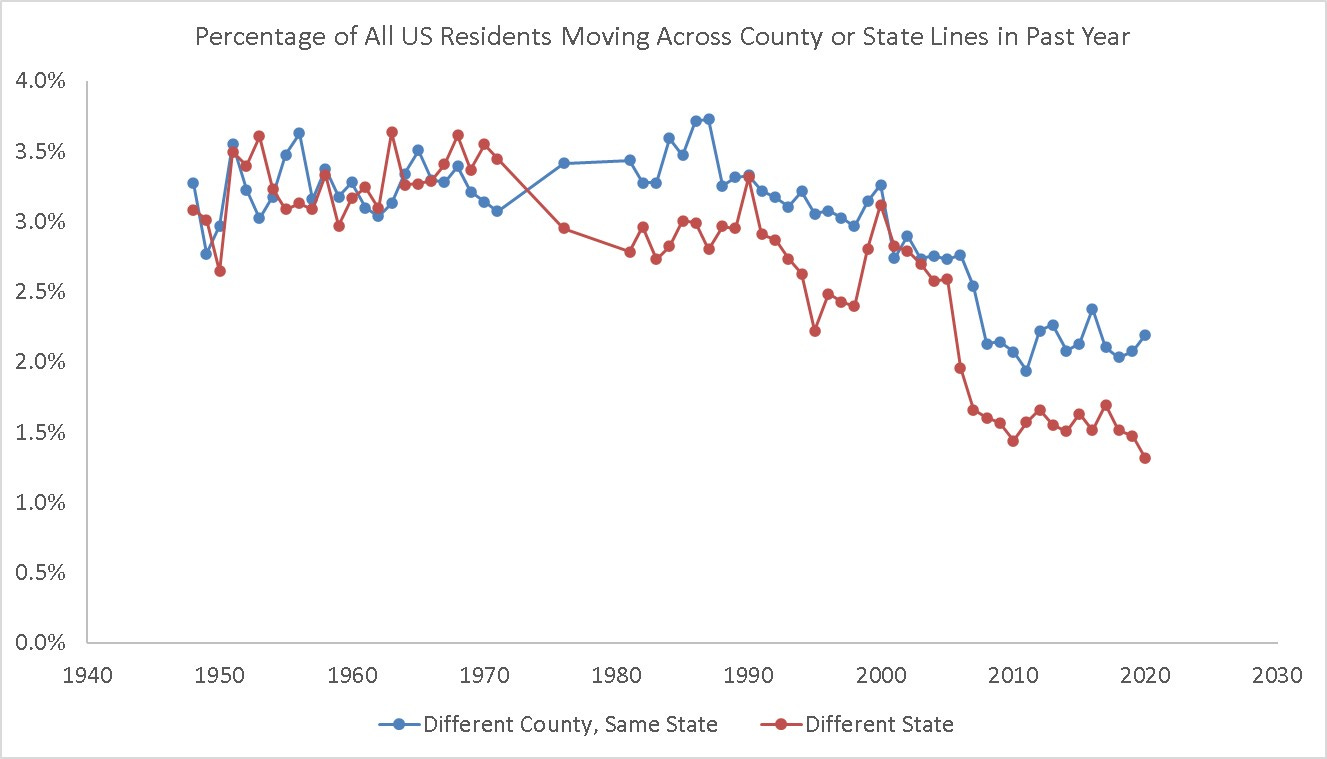

Moving, in any form, just doesn’t happen much anymore.

Only about 9% of Americans of all ages moved between March 2019 and March 2020, down from a peak of more than 20% in the early 1980s. The percentage moving across state lines is down to just over 1%. Nearly twice as many people moved across state lines in 1999-00 (8.2 million) than in 2019-20 (4.2 million), despite the population being nearly 20% lower in 2000.

This might come as a surprise, given high-profile headlines of people fleeing New York in the early parts of the pandemic and companies like Tesla and Oracle moving headquarters from California to Texas. It’s true this data ends in March 2020, just before the pandemic began. But there’s no indication that the pandemic reversed the broader slowdown in moves. If anything, people moved less during virus spikes.

In fact, Census population growth data through July 2020 show growth slowing across the US, with a few Sunbelt states like Texas seeing increases. Data from moving companies like United Van Lines and real estate listings companies like Zillow and ApartmentList, find that overall moves are down while movement from the center of megacities like New York and San Francisco to those cities’ suburbs rose in the summer. And there’s also evidence showing many pandemic-prompted moves were temporary.

Broader forces have been driving mobility rates downward for at least the past 20 years, and pandemic-driven trends are unlikely to change the long-term decline. Part of the drop is the aging population; the peak age for moves is in the late teens to early 30s, declining rapidly after 40. Still, movement trends continued downward through the 2000s and 2010s, just as the large millennial generation reached their most likely window for moving. Movement among 20-somethings, while still the highest among age groups, remains down as well.

Economists have found a few explanations for the decline in moves beyond aging:

The rise of two-income households, where spouses are relatively evenly matched in middle-income jobs, makes movement for one salary to voluntarily forgo another less beneficial.

The types of jobs for non-BA holders that used to be available in cities, particularly traditional manufacturing, are less and less available. They’ve been replaced with service-sector jobs in food services or warehousing, which tend to be lower paid and less secure.

At the same time, housing prices in growing markets have continually outpaced inflation, due to a slowdown in new development caused by regulatory land-use hurdles, increasing demand for existing units, and the fact that fewer people are moving, which means fewer available housing units.

For those with lower incomes, or who live in regions where housing prices never quite recovered from the previous recession, “home lock” is the primary issue. Negative home equity, and local- or state-dependent housing subsidies, make leaving unaffordable.

Deeper reasons to stay put don’t often show up in policy white papers. The type of people who write about movement trends are an especially mobile group - academic and media careers for the most part require that. But the fact remains that half of Americans live within 30 miles of where they were born. Benefits like childcare from extended relatives, stronger ties with local friend networks, and deeper community ties are hard to quantify but compelling.

Research from the Federal Reserve of New York found that people were willing to give up, on average, 30% of their income to stay close to family. The research breaks people into three groups - the mobile (38% of the population), the stuck (15%) and the rooted (47%). While policies to encourage geographic mobility focus on the benefits of moving for the “mobile” and the potential benefits for the “stuck,” the “rooted” make up nearly half of the population.

From a national perspective, encouraging mobility allows for economic efficiency. Talented workers from throughout the country will be more easily matched with jobs that maximize their skills and comparative advantages if they are able to move to the markets where those skills are most in demand. This mobility compounds, turning metros and regions with clusters of the top talent in any industry into magnets for more top talent. Economists, never known for their lyricism, call this “agglomeration.”

Hyper-agglomeration in the tech industry has created “supercities” in the United States. About 90% of all “innovation sector” jobs are in one of five metros. This explosive economic growth has its own challenges for these metros, particularly rising housing costs when coupled with barriers to new housing construction. But many regions would gladly trade the challenges of rapid growth for the challenges of managing decline in areas where now-declining industries once agglomerated.

The increased concentration of elite and highly educated workers goes beyond tech. Many neighborhoods in major cities are now “Ivy League superblocks,” where high percentages of not only graduate degree holders, but degree holders from the highest-ranked universities, live. This trend adds to the hardening of social divides between smaller and larger regions.

In the regions left behind, “brain drain,” when mobile and talent people move for better opportunities, can set in, especially if no new industry cluster backfills the regional economy. Oren Cass has characterized this process as elite higher education’s “strip-mining” of the United States for the best talent, which usually winds up settling in one of the top 10 metros in the country. While this framing begins with legitimate concern, it’s unclear what policy action might stem this tide, or even if it is a tide worth stemming.

The best hope for regions experiencing brain drain is to appeal to the “rooted” group and to make it easier for the talented among them to stay, or to make it worth their while to bring skills earned elsewhere back.

With the large millennial generation now reaching its 30s, and the largely successful experiment in mass remote working spurred by the pandemic, small metros should consider opportunities to appeal to major employers in growing industries, and the regional natives who hold influential positions within those employers, to consider outpost or remote working opportunities. One successful example is Google’s White River Junction Vermont office. The Center on Rural Innovation and its Digital Economic Development programs for rural economies offer some blueprints for potential rural tech growth.

There are, of course, costs to staying put. For the “stuck” those costs are compounding, even beyond generations. One study from the United Kingdom found that people born in the global city of London earned on average 10% more over their lifetimes than those born in the port city of Liverpool. For the truly “stuck,” policies that support moving to opportunity at the neighborhood level within metro areas have led to some success.

Ultimately, though, regional economists like Tim Bartik argue that bringing jobs to people is a more sustainable and equitable goal than moving people to jobs. Reducing the barriers to mobility for the “stuck” and leveraging the community knowledge and engagement of the “rooted” can create the types of places the truly “mobile” want to live and work.

2. California Zoning

If you want to see the future of the country, look at California, or so the old saying goes. Lately, that future has not looked too bright when it comes to livability. Housing costs, especially in San Francisco, have skyrocketed; wildfires have encroached on large swaths of exurban homes; and the state began to lose overall population in 2019.

Housing advocates place the blame on NIMBYism, an acronym standing for “Not In My Backyard.” NIMBYs, their opponents say, are a very cross-partisan coalition of environmentalists, preservationists, and homeowners with one uniting purpose - to oppose new development in their neighborhoods, or in some cases, any neighborhood change at all. Added up across thousands of neighborhoods, NIMBYism leads to a lack of new housing supply, which drives up rents and prices and pushes newcomers further and further into the suburbs and exurbs, many of which are in fire-prone areas.

California contains, some say, the most virulent strain of NIMBYism, and its negative effects are most visible in San Francisco. The opposition YIMBY movement (“Yes In My Backyard”) scored a victory this week not far from San Francisco.

Sacramento, the state’s capital, officially ended single-family zoning. That means that four-plexes can be built anywhere in the city, “by right” - with no zoning approvals and no planning board meetings. Single-family homes can and will continue to be built, this simply allows four-unit buildings to be built in areas formerly limited to single-family homes. Mayor Darrell Steinberg noted the decision was directly rooted in increasing equality of opportunity. “Everybody should have the opportunity to not only play in Land Park but to live in Land Park,” he told the Sacramento Bee.

While not a panacea for the housing affordability crisis, the end of single-family zoning is an important step forward. Minneapolis became the largest American city to end the practice this year. To give you an idea of how widespread single-family zoning is, fully 15% of land in our densest American city - New York - is zoned for single-family homes.

For my Charlotte-centric readership, here’s a photo of a four-plex in Dilworth. Pre-World War II neighborhoods like Dilworth and Plaza-Midwood contain many of these alongside single-family homes. You’d be hard-pressed to argue that they hurt property values there.

3. Optimism for Electrical Vehicles

President Biden announced plans this week to move the federal government’s fleet of 645,000 vehicles to electric engines. While the timeline for the shift remains uncertain, the move taps into a new political appetite for environmental consciousness. And unlike previous clean energy stimulus moves, the economics of electric vehicles are much more favorable. The cost of EV batteries has plummeted about 88% from 2010 to 2020 and continues to drop. Bloomberg estimates that battery pack prices will fall below $100 in 2024. At that point, EV costs will become comparable to internal combustion engines.

International EV maker Arrival announced plans to expand into the US recently. They’ll be establishing their first microfactory in Rock Hill, SC, where they will build electric buses, and their North American headquarters in Charlotte. With Arrival’s recent round of $118 million in VC funding from BlackRock, it’s clear that there’s renewed optimism in the future of the EV market.

Last week, Arrival North America CEO Michael Abelson appeared on the Charlotte Regional Business Alliance podcast along with Richard Colley, a representative from Arrival’s Public Policy team, myself and Alliance colleague Eileen Cai.