The Long and Short of the Labor Shortage

There are many more factors at play than unemployment benefits in the hiring crunch. Some of them are short-term. But some of them are here to stay.

Last week was the last of the “off-season” in the Outer Banks, though North Carolina is usually warm enough to make May trips common. Judging by the crowds on some beaches, it’s going to be a busy summer.

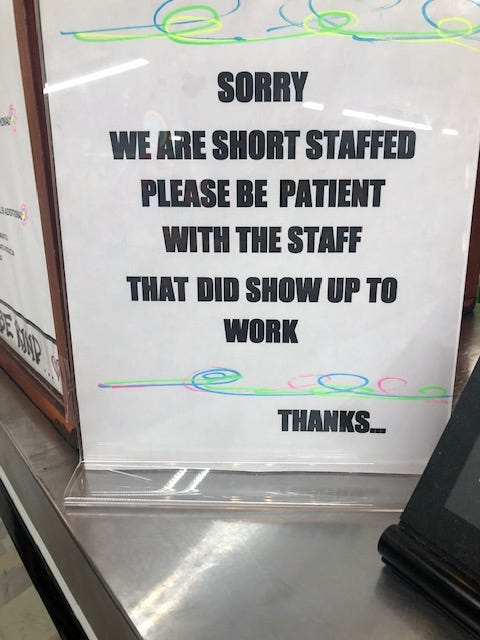

The Outer Banks are also a great place to observe the hiring crunch facing all service sector industries as the post-pandemic economy revs back up. Nearly every restaurant or convenience store had a “now hiring” highway sign or an apologetic notice on the counter (some more colorful than others) indicating longer wait times and more self-service. The Dairy Queen in Kill Devil Hills advertised a $12.99/hour starting wage, and only a handful of full-service restaurants were open on Mondays and Tuesdays.

It’s not unusual for restaurants in remote and seasonal vacation towns to pay a premium for labor or to take a while to ramp up hiring in the first few weeks of the summer. But something about this year is different, in the Outer Banks and beyond. After a year of fits and starts following the complete shutdown of Spring 2020, economic activity came roaring back around March 2021. First, demand for goods left suppliers scrambling to meet new car orders. Now, as half of U.S. adults are fully vaccinated, demand for in-person services like restaurants and travel has led employers to get creative on staffing up for newly reemerged crowds.

It’s also not unusual for employers to report labor shortages. Though this time the data seems to align with the anecdotes and there’s no question that the service sector is struggling to hire. What is up for debate are the causes of the shortage and whether or not these factors are temporary blips of an economy recovering at breakneck speed, or deeper forces representing structural economic and societal shifts.

April’s jobs report, which showed the economy had added a weaker-than-expected 266,000 jobs, poured fuel on the fire of the debate over the role of unemployment benefits in keeping workers sidelined. A closer look at the April report, though, shows that low-wage jobs grew the fastest, with leisure and hospitality adding more than 330,000 jobs. Losses, on the other hand, were felt in manufacturing subsectors like automotive manufacturing, where supply chain shortages are limiting production, and in grocery stores and courier services, which would expect to see demand decline as more in-person services reopen.

If unemployment supplements were the primary driver of the disappointing jobs report, the lowest wage jobs would likely be the most impacted. The May jobs report, out this Friday, should give us more information on whether the April report was just an anomaly. Regardless, 24 states ended their participation early in the additional $300/week benefit provided by the federal government as well as the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) for self-employed gig economy workers who would otherwise not qualify for unemployment. Overall, about 16 million people remain on some form of unemployment assistance, including about 6.5 million gig workers on PUA. Many states planning to keep the federal benefit until its Labor Day expiration have reinstituted requirements that recipients search for a certain number of jobs each week to continue to receive the benefits.

Unemployment insurance benefits, child care challenges, and lingering fears of COVID are all playing a role in the speed and trajectory of the economy’s reopening. And there’s been a robust debate on each of these points.

A couple of trends have gotten less attention but are longer-standing and likely to have deeper, more structural impacts on the labor market for leisure and hospitality jobs.

Immigration has declined precipitously - This was a pre-pandemic trend. After peaking at more than 1 million net new international migrants to the United States in 2015 and 2016, immigration has fallen each year since, due to a combination of tighter immigration restrictions and travel challenges. Between July 1, 2019 and July 1, 2020, less than 480,000 net new immigrants arrived in the United States. And with more travel restrictions in place in the later part of 2020 and early 2021, slower immigration is likely to continue. This limits the supply of labor in the hospitality and construction industries, particularly the supply of international students on J-1 and other visa programs who often fill seasonal jobs.

Restaurant workers ‘pivoted’ during the pandemic - With restaurants in much of the US closed or limited in their capacity to serve dine-in guests, many restaurant workers shifted to businesses that stayed open during the pandemic - like construction or building supply stores. The higher pay in construction and arguably better work-life balance in some parts of retail has, some restaurant recruiters say, left former restaurant workers with better options. With demand for housing reaching historic peaks, construction-related industries could see their own hiring boom soon as well, giving former restaurant workers less incentive to return.

There are fewer young people and young people are less likely to work summer or part-time jobs - High school and college-age workers are a mainstay of the restaurant, retail, and hospitality workforce. More than 33% of restaurant workers and 25% of retail workers are under 25, according to analysis by labor analytics software company EMSI. With a continually dwindling birth rate, declines in immigration, and a drop in the number of high school students working part-time jobs, restaurant owners and managers may continue to find hiring difficult. That will be especially true in rural areas, where the youth population has declined most drastically. EMSI’s new report on the “demographic drought” provides more details on the broader workforce and labor implications of what they call a “sansdemic.” On the positive side, the remaining teenagers looking for work have found more options and higher pay.

Source: EMSI from “The Decline of Young People in America” Transit cutbacks in major cities and rising rideshare costs have made it harder to get to work - With office workers commuting less and in-person entertainment canceled, many major cities cut back on transit service. Most famously, the New York City subway suspended its 24-hour service. But other large metros with less reliable service to begin with cut back. Even before the pandemic, Uber and Lyft had become a lifeline of last-mile transportation for bar and restaurant workers with unpredictable or off-hour schedules. Now, costs for rideshare are increasing as well to nearly double pre-pandemic rates, according to some New York City workers. (This is not just an NYC issue. Anecdotally, the quoted price for a 5-mile Lyft route I often took before the pandemic in Charlotte is up about 60%). The lower availability of ridesharing is a labor market issue in itself, with many ridesharing services reporting struggles to hire drivers, leading to higher costs and incentives for the drivers that have come back. As self-employed contractors, rideshare service drivers qualify for unemployment insurance through the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, unlike in previous recessions. Like restaurant workers, though, it’s likely that many rideshare drivers shifted to steadier industries during the peak of the pandemic while demand for ridesharing was low.

As COVID cases continue to drop and vaccination rates continue to climb, hiring will pick up. The extent to which unemployment benefits will affect the labor market’s recovery is likely to be temporary and will pale in comparison to the broader demographic, philosophical, and lifestyle shifts that will unfold over the coming decades. Whether or not the COVID-19 pandemic represents a “great reassessment of work,” will depend on the interplay of employers, consumers, and workers. With consumer demand increasing and the pool of willing workers smaller than in years past (for whatever reason), labor’s ability to push wages and benefits higher in lower paid industries is currently strong. Some combination of higher wages (and thus consumer prices) and automation of service levels seems likely. That’s not a bad thing, as labor-saving investments will be necessary in regions with fewer people, and embracing innovation is crucial for long-term competitiveness. Consumers have shown little hesitation in accepting these innovations in grocery stores and fast food chains.

Ultimately, the labor market challenges we face today are the result of interconnected forces, and they can’t be boiled down to simple explanations. Rapid transitions have a way of smoothing themselves out, but structural changes will have greater and longer-lasting impacts.

Thanks. Nice to read an assessment not based purely on ideology.