Opportunity, Mobility, and Safety - Sept. 7, 2022

Walking is getting more dangerous in the United States. That's bad for our health and our economy.

I've been taking a closer look at driving habits lately. If you do any walking or cycling around an American city, and you have any self-preservation instincts at all, you really have to. Aside from a few dense downtowns, Americans tend to view pedestrians as pests slowing down the flow of more legitimate traffic or objects of pity too poor, or perhaps too addled, to drive. Show up somewhere in the South using a bus or a bike and you’re likely to get raised eyebrows and probing questions about potential drunk driving violations. Walking is a leisure activity you drive to the park to do.

My regular 10-block walk from work to a parking garage across Uptown Charlotte, North Carolina (an area with ostensibly pedestrian-friendly design) is punctuated with red-light runners and vehicles turning into the crosswalk. Not to mention cars parked on sidewalks or blocking streetcar tracks. Occasional cycling trips are slightly less harrowing, but mostly because of newly developed trails and separated bike lanes. You still have to look out for cars drifting into the plastic posts lining the lane or turning without looking.

It's hard to talk about the downsides of driving without feeling a bit hypocritical. The car has become so engrained as part of American culture - a symbol of freedom and a milestone of maturity. Taking the landscape of most post-WWII American cities as a given - the sprawling spaces between destinations, wide roads with limited sidewalks, subsidized and readily available parking combined with scant and often unreliable public transportation - the private car is almost always the most convenient option. Despite our reasonably strong efforts to live within walking distance of most necessities, work and family obligations plus leisure travel still rack up a few thousand miles on our Honda CR-V's odometer each year.

But it's also hard to look at the statistics and dismiss the United States’ comparatively dismal record on highway fatalities as simply the natural costs of a modern lifestyle or more ethereal idea of “freedom.” Reckless driving has gotten a lot of attention since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. But even before 2020, drivers and pedestrians in the United States have become less safe compared to the rest of the developed world.

While per capita fatalities have long been elevated in the United States, improvements in traffic safety seem to have stalled since the 1990s, and in many cases they have backtracked since the mid-2010s. France, for example, had a higher rate of traffic fatalities than the US in 1990, despite fewer miles driven per capita. By 2019, Americans were more than twice as likely to die on the road than French people, whether drivers or pedestrians. And by 2021, the risk of death was nearly triple in the United States than in France.

Americans get defensive when you mention the downsides, or as economists call them externalities, of driving. And a typical response to these fatality comparisons goes something like this: “Americans have to drive more because our country is bigger. We have to cover more distance.” And while it’s true that Americans drive more miles per capita, most car trips are astonishingly short. According to the US Department of Transportation, more than half of all car trips cover less than five miles, and a full 20% of all car trips in the United States cover less than one mile - a leisurely 15-20-minute walk for most able-bodied adults. Similarly vast countries such as Canada and Australia have seen declines in traffic fatalities that mirror European counterparts more closely than the U.S.

This explanation also masks the why behind Americans’ tendency to drive, even for these short trips. Americans drive more and more often than their counterparts in other nations. And by the same token, we walk far less. But looking at pedestrian deaths by country reveals that American pedestrians are more likely to be killed walking than French pedestrians. This is another change since 1990, when France and the US were more or less even in terms of pedestrian deaths. And in 1975, walking in France was more deadly than in the US, according to an analysis by the Urban Institute.

Smartphones, SUVs, and Speed Cameras

It’s tempting to explain away the rise in fatalities to distracted driving and smartphone use. There does seem to be an uptick in fatalities in the early 2010s, around the same time as smart phone use reached critical mass. But the growth of the smartphone was global; the rise in fatalities was limited to the U.S. I see no evidence that the French or Canadians or Australians are inherently more judicious smartphone scrollers than Americans.

The differences are clear - enforcement, regulation of externalities, and improvements in street design have coalesced to create safer streets elsewhere, while opposite trends in the United States have led to worsening safety conditions. Speed cameras with sufficiently high fines, taxes on the heavyweight vehicles more likely to cause deadly collisions, and increased pedestrian- and bicycle-only streets in central cities have curbed opportunities for pedestrian collisions in many other wealthy countries. At the same time, fuel economy standards that tied mile-per-gallon minimums to vehicle weight have encouraged the promotion of larger frames and sped the transition from sedans to SUVs, which have more blind spots and higher grills that shift the impact zone in collisions with pedestrians from the legs to the vital organs of the chest and head.

Why Walking is Not a Luxury Good

Political pushback and lawsuits against speed-detecting and red-light cameras have led to spotty enforcement of traffic rules. At the same time, the push of young professional millennials into previously disinvested urban neighborhoods through the 2010s shifted the popular image of pedestrians to an affluent bunch. Through the windshield view of many urban politicians, advocacy for bike lanes and micro-mobility options like scooters and e-bikes seemed a luxury concern.

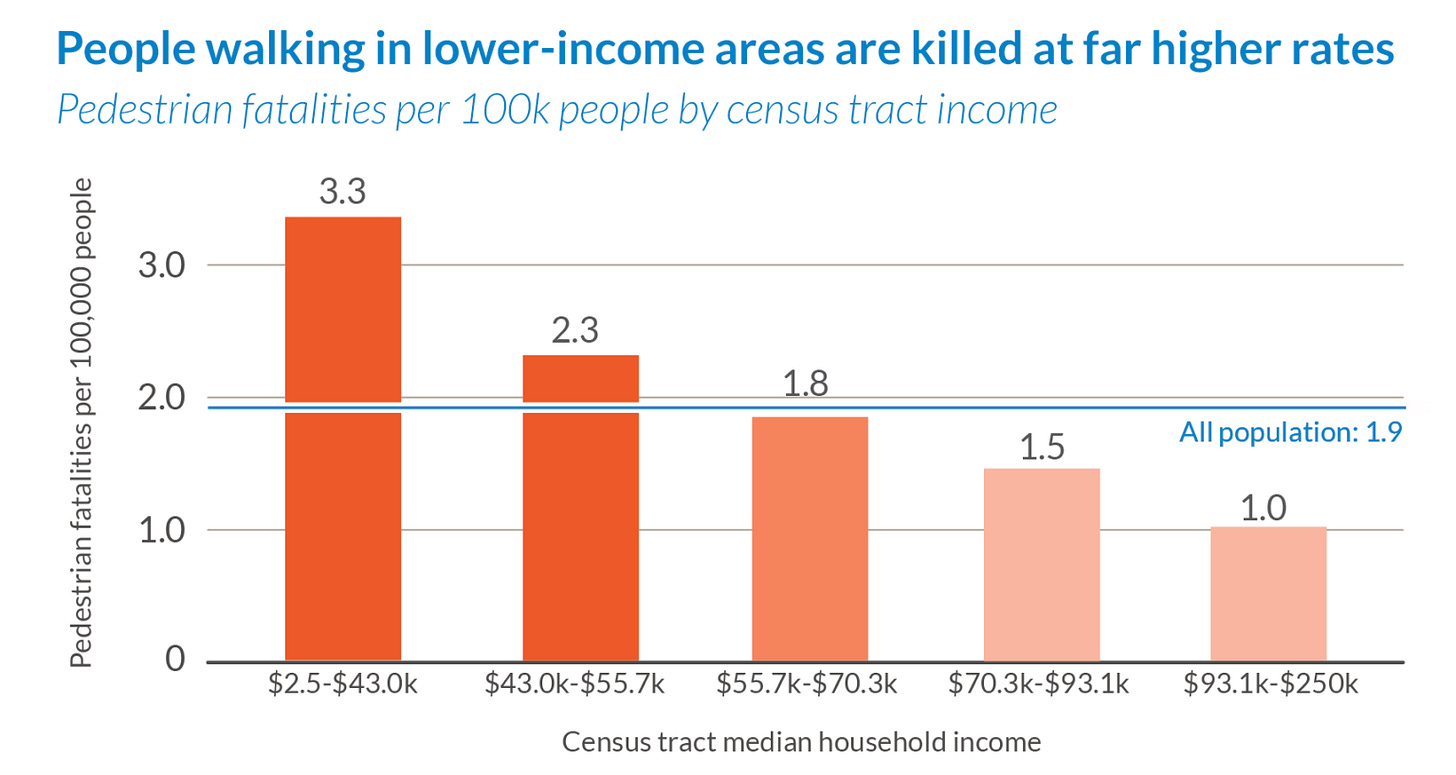

This perception masked reality. Those who rely on walking or biking are far more likely to be low-income workers. Data from the 2020 Census reveal that of the 4 million Americans who walk to work, 65% make $35,000 or less. Low-income pedestrians bear the brunt of fatalities on unsafe streets. Deadly pedestrian collisions are more than three times as likely in lower-income neighborhoods than higher income ones, according to a recent analysis by Smart Growth America.

A look at the map of the deadliest places for pedestrians aligns closely with the map of the fastest-growing regions in the country. These include mostly small-to-midsize cities in the South and broader Sun Belt, and the suburbs and exurbs of larger Sun Belt cities. The coronavirus pandemic and response has only heightened this trend. As development has moved further South and further into the exurbs, aging housing stock in auto-oriented, first-ring suburbs has become home to more low-income workers, a trend that can only harden these deadly patterns without intentional efforts at improved road safety.

Walkability, Mobility and Opportunity

The map of pedestrian deaths overlaps considerably with a third map – the map of areas with the lowest levels of socioeconomic mobility, according to the 2014 Chetty study that tracked individuals born in the early 1980s and compared their household income and location as children to the same information at age 30. Those born poor in these places were much more likely to remain poor.

A closer read of the study revealed the driving factor behind economic mobility – commute time. Those from households in the lowest 20% of the income distribution who had better access to nearby jobs and educational opportunities were far more likely to move into the highest 20%. And places with functional transit systems and denser development supported this higher level of socioeconomic mobility because, among other reasons, families could reach destinations affordably and conveniently, without the upfront investment or ongoing maintenance costs of a car.

The relationship between commute time and socioeconomic mobility is strong, and the state of sprawl in American cities that grew after the 1950s seems so intractable, that some researchers have suggested subsidizing car ownership for low-income families as the only immediate solution. Some smaller cities are experimenting with ride share vans as replacements for some bus routes.

Opposition to subsidies for individual car ownership seem to focus on concerns of climate change, which has opened these opponents up for claims of hypocrisy. “Should only the comfortable be allowed to drive polluting cars?” The increased danger presented by more cars on badly designed roads, heightened in low-income neighborhoods, rarely enters the discussion. Subsidized ride-share systems seem more universally valuable, as they can also be used by the disabled and those too young or old to drive.

Increasing the Supply of Walkable Areas

The focus on immediate mobility – both physical and socioeconomic - is crucial. But these immediate steps don’t have to conflict with longer-term goals of retrofitting our car-dependent landscape to something more accessible, and safe, for all. The American Enterprise Institute’s recent analysis on Walkable Oriented Development offers one model for incremental redevelopment with the potential for transformational impact. The report’s focus is on adding housing units through targeted up-zoning in places within walking distance of existing commercial nodes. The Institute estimates these goals might add as many as 2 million new private homes over a 10-year period with limited government subsidies.

This dual goal of reducing housing scarcity and encouraging the most basic form of mobility – walking – won’t look exactly like traditional downtown development. It will include things like reducing parking ratios at local strip malls and constructing walkways connecting cul-de-sacs. Many of the walkable areas identified might come as a surprise in areas with poor street connectivity. There are places, for example, where a greenway through a storm water easement might shave a half-mile and a sprint across a six-lane arterial off the walk from a neighborhood to the grocery store.

Even these small changes won’t come without opposition, but they’re worth considering for the livelihoods they might improve, and the lives they might save.

Further reading

Dangerous by Design 2022, Smart Growth America

Angie Smith, Right of Way: Race, Class, and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America